“Do the best you can until you know better. Then, when you know better, do better.” Putting poet Maya Angelou’s popular wisdom into practice is key to realizing achievable gains in how students learn. Few know this better than Laurence Holt, who has spent the last two decades leading innovation teams in for-profit and nonprofit K-12 organizations. Most recently, he authored The Science of Tutoring, which is available for free and dives into how tutoring practice can go beyond surface-learning to better explore deep-learning concepts. Holt talks with 5 Questions about his book’s innovative blueprint for improving how students learn in the United States.

What is the science of tutoring?

I lived for a couple of years in Paris. The mornings were luxuriously free from interruption, since everyone in the U.S. was asleep. It was as if I had been in a carnival crowd and turned abruptly into a peaceful side street. I decided to write a piece about tutoring. Given the huge upsurge in schools providing tutors across the country, I thought someone should try to get to the bottom of what makes it work. Surprisingly, my research didn’t turn up any clear answers. So, now I was really hooked. I began calling up researchers who have studied tutoring, which is not many. It felt a little like a conspiracy of silence.

Still, a story began to emerge, and the piece grew from an article into a thin book structured a bit like a detective story. For instance, we know tutors spend a great deal of time explaining a topic. But researchers have known for years that explanations typically have little impact on learning.

The first half of the book became a compilation of counterintuitive findings—on explanation, scaffolding, feedback, and questioning. They all have a role in good tutoring but, in each case, it’s not quite what you think.

Why is it important now?

Three reasons. First, and most obviously, tutoring is a bigger feature of the K-12 landscape than it was pre-pandemic, and it seems likely to remain so, despite funding cliffs, because it works most of the time. So we want to know how to make it work more of the time, and work at scale. We can’t do that if we don’t understand the active ingredients of effective tutoring.

Second, there is a lot of talk about generative AI tutors. The AI field advances by having clear targets, such as “beat humans at chess”, “beat humans at Go”, “predict protein folding structures.” Clear targets are not something we do well in K-12. Most of the people working on AI tutors seem to think the goal is asking questions and giving explanations. But that’s not at all what good tutoring is.

Third, we need more innovation around tutoring. For instance, what is the optimal blend of human and machine? Humans are expensive. Machines work for only 5% of learners.

Most of the people working on AI tutors seem to think the goal is asking questions and giving explanations. But that’s not at all what good tutoring is.

What's Been the Biggest Surprise So Far?

The first half of The Science of Tutoring arrives at the conclusion that the reason tutoring works is perhaps not so surprising: kids do more cognitive work when a tutor is present. It’s just difficult for the student to hide. And more cognitive work inexorably means more learning.

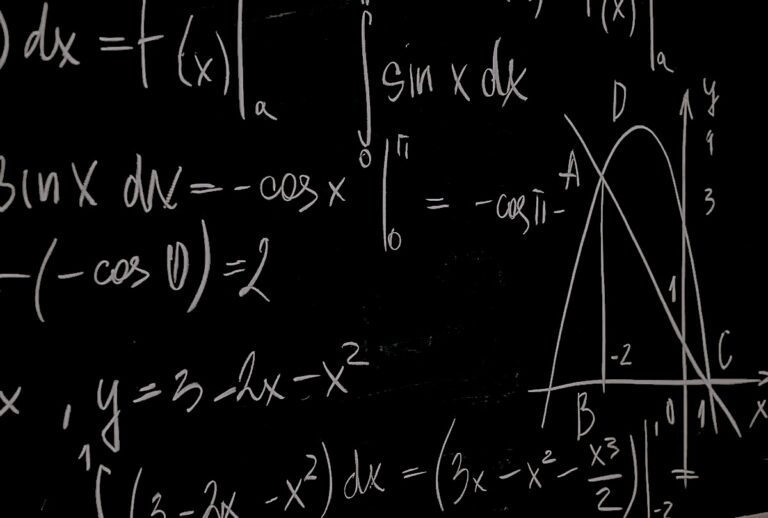

But there is more to the story. Buried in a 63-page paper by Micki Chi, a professor at the Institute for the Science of Teaching and Learning, I found an anomaly, like the distant yap of a small dog accidentally locked in a closet. What, Chi asked, if you distinguish surface learning from deep learning? Tutoring works for surface learning-—such as the procedure for calculating slope. When measures of deeper, conceptual learning are used, though—such as what slope means in this particular context—tutoring typically has no effect.

This doesn’t get reported because, on the tests we use to evaluate math ability, it’s okay to flip and multiply fractions without any understanding of why that works. But the finding led me on a long journey to uncover the tutoring moves that really would lead to deep learning, if tutors adopted them.

Where do you see tutoring in five years?

The secret to deep learning, like the secret to a good story, turns out to be (1) a conflict or impasse that leads to (2) a resolution. And in learning, as in a good story, you do not want to rush either of them. The impasse has to feel like a genuine impasse, which it won’t if it is not properly established or if it is, from an abundance of eagerness, resolved too quickly. The resolution, when it comes, has to come from the actions of the main character. In learning, the main character is the student.

My hope is that, in five years, we will have trained tutors – and teachers – in this technique. It requires you to stop and understand student thinking. I recently saw a good example: a student was asked “What is 15 – 6?” and answered “Is it 11?” The recommended response from an expert tutor was to explain how to do the subtraction. But far better would be something like, “That’s interesting, how did you get 11?” Or, to generate an impasse, “Okay, then if you add the 6 back again, what do you get?” Many learners will upgrade their thinking right in front of you.

Training humans is hard, so maybe AIs will get there first, though right now the way they are trained is equally problematic: they like to be agreeable and avoid confrontation, which is quite the opposite of a good, deep tutor. That’s easy to address once the AI-builders understand the problem.

My hope is that, in five years, we will have trained tutors – and teachers – in this (deep learning) technique. It requires you to stop and understand student thinking.

What Else Should People Know?

The way the book ends has sparked some controversy. I knew many readers would be more interested in classroom teaching than in tutoring, but answers to what makes classroom teaching effective are even harder to come by than those for tutoring. The final paragraph reads, “If there is a way [deep learning] can be achieved in a classroom of one teacher and thirty students, I have no idea what it is. Tutoring may be the only reliably effective mechanism available to us.”

People have pointed out that there are certainly examples of excellent classroom teaching. But, of course, I meant “reliably achieved at scale…” I hope someone, somewhere—perhaps in a garret in Paris—is working on that book.