Speech-to-text (STT) models suffer from a significant performance gap when applied to child speech compared to adult speech. State-of-the-art STT AI models achieve as low as 5 percent Word Error Rate (WER) on adults in real-world settings. The same models achieve 11-18 percent WER on children, but performance gets even worse on younger children: 15 to 21 percent WER on young children (6-10) and up to 35 percent WER on kindergarteners (4-6). Put differently, research shows a 30 percentage point gap between WER on kindergartens vs adults.

Finetuning can improve this dramatically, using only parameter-efficient finetuning, which uses minimal compute resources. Research conducted by The Learning Agency achieved a 12 to 30 percent reduction in the word error rate on a datasets of child voices, suggesting that substantial improvements in speech-to-text for child voices can be made through traditional finetuning procedures.

However, even with finetuning, current approaches to child-centric STT fall short of performance on adults. Aside from further finetuning efforts (which may show improvement with more or better data), other possible improvements include self-supervised approaches (making use of unlabelled speech data) and personalized models.

Current STT Models and Performance

State-of-the-art STT models generally utilize deep learning approaches, often employing recurrent neural networks (RNNs), convolutional neural networks (CNNs), and increasingly, transformer-based architectures. These models are trained on massive datasets of speech and corresponding text.

When considering real-time systems, a key challenge is balancing accuracy with computational efficiency and latency. Many high-performing offline models are too resource-intensive for real-time applications, leading to a trade-off in performance.

Performance on Adult Datasets

For adult speech, current state-of-the-art STT AI models achieve impressive WERs. Our benchmark standard is 5 percent WER in real-world settings. Notable models Amazon Transcribe, Azure Speech-to-Text, and OpenAI’s Whisper, which all fall within this band on real world scenarios.

Performance on Child Datasets

The performance of STT models significantly degrades when applied to child speech. These very same models yield:

- 11-18 percent WER on (all) children

- 15-21 percent WER on young children

- Up to 35 percent WER on kindergarteners

when applied to similar real world scenarios. This poorer performance can be attributed to several factors unique to child STT tasks:

- Difficulty in identifying children’s voices resulting from a variety of speech patterns

- Higher variability in pitch and speaking rate: Children’s voices exhibit wider fluctuations.

- Less distinct articulation: Children often speak less clearly.

- Limited vocabulary and simpler sentence structures: While this might seem to simplify the task, it also means standard adult language models might not capture the nuances of child language.

- Acoustic environment variations: Children’s speech is often captured in noisier or less controlled environments.

- Less child-specific speech data renders off-the-shelf models heavily under-sampled when applied to child speech.

| Study | Adults (WER) | Ages 10+ | Ages 6-10 | Ages 4-6 | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shivakumar et al. (2020) | — | ~11% (ages 11-12) | ~18% | ~34% | Shows age-dependent variability decreases sharply after ~12. |

| Kathania et al. (2022) | — | ~13% (ages 10-13) | ~21% | ~35% | Highlights formant modification for younger children; dialect-sensitive. |

| Johnson et al. (2022) | ~5% | — | ~19% (AAE/Southern) | — | Dialect augmentation reduces gap by ~15% relative WER. |

Model Bias

Research also indicates a disparity in STT model performance across different English accents, with models often showing lower accuracy for non-standard or regional accents compared to Standard American or Standard British English. This problem is likely amplified in child ASR, as children’s articulation interacts with dialectal variation, leading to compounded errors. For example, African American English (AAE) or Southern U.S. English speech often results in higher error rates in adults, and preliminary findings suggest the divergence is even greater in children. More systematic research on dialectal impacts in child ASR is needed.

Research also indicates a disparity in STT model performance across different English accents, with models often showing lower accuracy for non-standard or regional accents compared to Standard American or Standard British English. This problem is likely amplified in child ASR, as children’s articulation interacts with dialectal variation, leading to compounded errors.

Factors Influencing Child ASR Performance

Age

WER varies substantially across fine-grained age brackets. Children between 4-7 often show the highest error rates due to developing articulation and vocabulary. Performance begins to stabilize after age 10, though complete alignment with adult ASR typically occurs around ages 12-13.

Setting

Data collected in schools vs. homes can affect outcomes. Classroom recordings (e.g., the MyST dataset) often include background chatter and structured speech, while at-home recordings may include more spontaneous, noisy, or conversational data. Studies indicate that child ASR is more sensitive to environmental setting than adult ASR, with school-based recordings yielding more predictable results.

Methodology

The elicitation method has significant influence on WER. Structured read-alouds produce lower WER than free-play speech, storytelling, or interviews, since the latter contain more disfluencies, repetitions, and child-specific vocabulary. Research suggests that read-aloud tasks yield performance most comparable to adults, whereas spontaneous conversation remains the most difficult.

Background Noise

Children’s ASR models are disproportionately affected by noise compared to adults, partly due to higher vocal pitch and less stable articulation. While adults’ WERs may rise moderately in noisy conditions, children’s WERs can double in the same environments.

Recording Length

There is no consensus on optimal segment length. Word- and sentence-level recordings are often used for controlled benchmarking, but paragraph-length or conversational data better reflect real-world use. Some studies suggest sentence-level recordings strike the best balance for training children’s ASR, while adults’ models perform consistently across lengths.

Finetuning pre-trained adult STT models on child-specific datasets has shown to dramatically improve performance. Parameter-efficient finetuning minimizes computational resources at little or no cost to accuracy.

The Impact of Finetuning

Finetuning pre-trained adult STT models on child-specific datasets has shown to dramatically improve performance. Parameter-efficient finetuning minimizes computational resources at little or no cost to accuracy, so it is often favored over more laborious methods. Low-Rank Adaptation, or LoRA, is by far the most common method of finetuning.

These methods can lead to approximately a 30 percent improvement over baseline models, as seen in recent research conducted by The Learning Agency. This results in an improved 13 to 21 percent error rate across different child age groups. This highlights the importance of domain-specific data for achieving better accuracy. Despite these improvements, current child-centric STT approaches still fall short of the performance observed on adult speech for the same factors limiting off-the-shelf models.

This may be rectified with access to better data sources. While sources such as MyST offer annotated child speech in an educational context, sheer quantity limits what can be done to learn child-specific speech.

How should we measure STT tools?

There are a number of common measurements used to assess STT performance. These can be split into accuracy metrics and secondary metrics (latency, accessibility, etc.). We focus on accuracy as it is most important in educational contexts.

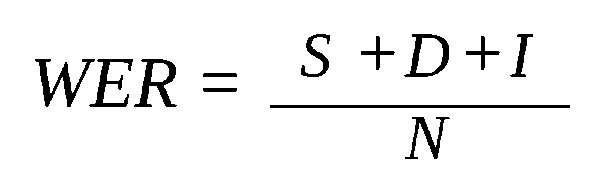

Word Error Rate (WER) is the most commonly used accuracy metric. WER is the length-normalized edit distance between the STT’s transcription and the ground truth. I.e:

Where S (substitutions), D (deletions), and I (insertions) are the three standard edit operations, and N is the number of words in the reference. Note that if more than one edit is required per word, WER exceeds 100 percent.

Critics note that WER doesn’t always align with human impressions of “good transcription”. For example, when using WER, etc., words are often stemmed and punctuation is removed, but these subtle differences are usually important in good transcription. Beyond WER, other metrics exist, although they are less commonly used. Character Error Rate (CER) is analogous to WER but operates at the character level, often used for languages without clear word boundaries, while Phoneme Error Rate (PER) measures errors at the phoneme level, providing fine-grained acoustic model evaluation. Semantic evaluations methods such as BLEU score and SeMeScore aim to measure meaning preservation, rather than mere word equivalency. While these metrics offer alternative perspectives, their adoption is less widespread than WER in the general STT research community, and their limited application restricts their usefulness as metrics.

While WER considerations largely overlap between adults and children, additional child-centric metrics may be warranted. For example, transcript readability or comprehension scores may be more appropriate for educational contexts. Metrics such as semantic preservation (BLEU, SeMeScore) may be especially valuable in evaluating spontaneous child speech, which often diverges structurally from adult language.

The pervasive challenge of limited child speech data presents a significant hurdle for developing accurate and robust STT technologies tailored for pediatric applications.

Promising Directions of Inquiry

Synthetic Data

The pervasive challenge of limited child speech data presents a significant hurdle for developing accurate and robust STT technologies tailored for pediatric applications. Traditional supervised learning approaches, which underpin much of current STT model development, are heavily reliant on vast quantities of meticulously annotated speech data, and finetuning on smaller volumes of data is often incapable of completely untraining tendencies learned in pretraining. The natural approach to this problem is to generate synthetic data similar to the lacking real data.

Self-Supervised Learning (SSL)

A promising paradigm shift addressing this data bottleneck is Self-Supervised Learning (SSL). Unlike supervised methods, SSL models are designed to learn meaningful representations directly from large volumes of unlabelled data, and, while there is a dearth of labelled child speech data, unlabelled data is much easier to find.

The core principle behind SSL involves creating a “pretext task” where the model predicts certain aspects of the input itself, thereby generating its own supervisory signals. For instance, in speech, an SSL model might be trained to predict masked segments of an audio waveform, reconstruct shuffled speech segments, or distinguish between original and augmented versions of the same audio. Through these self-generated tasks, the model learns intricate patterns and features within the speech signal, effectively capturing the underlying acoustic and phonetic structures without the need for human intervention or explicit transcriptions.

A unique advantage of this approach would be the ready application of existing data. Readily available child speech datasets such as MyST could be shuffled, for example, then a model could be pretrained to reconstruct the original MyST dataset.

Subsequently, these robust, pre-trained SSL models could be fine-tuned with much smaller, more manageable labeled datasets of child speech. This two-stage process – large-scale unsupervised pre-training followed by targeted supervised fine-tuning – could dramatically alleviate the burden of data annotation. The pre-trained representations would provide a powerful starting point, enabling the models to learn new tasks and adapt to specific child speech characteristics with significantly less labeled data.

Beyond a potential increase in accuracy as measured by average WER, personalized STT models may additionally solve problems of disparate performance across various groups, as each accent or speech impediment can be independently learned.

Personalized STT Models

The other distinct problem, the inherent complexity of child speech, requires a distinct solution. One promising direction is to personalize STT models to each individual speaker. While general models aim for broad applicability, more specific models can exceed general models on accuracy at the cost of a higher per-case cost in data and compute. This could significantly mitigate the challenges posed by the high variability in children’s voices, their unique vocabulary development, and individual speech patterns, but would require large volumes of data specific to that child.

Personalization can be achieved through various methods, including:

- Adaptive Learning: Models can continuously learn from a child’s speech over time, adjusting their acoustic and language models based on new inputs. This could involve techniques like online learning or incremental training, where the model updates its parameters with each new utterance.

- User-Specific Finetuning: Similar to the general finetuning discussed earlier, but applied at an individual level. A base STT model can be finetuned specifically on a small dataset of a particular child’s speech, leading to highly accurate transcriptions for that child. Datasets such as CSLU Kids and MyST, which contain repeated recordings of the same children across sessions, could support limited personalization experiments.

- Speaker Diarization and Adaptation: For scenarios involving multiple children or children and adults, personalized models could leverage speaker diarization to identify individual speakers and then apply speaker-adapted acoustic models. This ensures that the system accurately transcribes each child’s unique voice.

Beyond a potential increase in accuracy as measured by average WER, personalized STT models may additionally solve problems of disparate performance across various groups, as each accent or speech impediment can be independently learned.

Neil Natarajan

Sources

Ashvin, A., Lahiri, R., Kommineni, A., Bishop, S., Lord, C., Kadiri, S. R., & Narayanan, S. (2024). Evaluation of state-of-the-art ASR Models in Child-Adult Interactions (arXiv:2409.16135). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2409.16135

Fan, R., Balaji Shankar, N., & Alwan, A. (2024). Benchmarking Children’s ASR with Supervised and Self-supervised Speech Foundation Models. 5173-5177. https://doi.org/10.21437/Interspeech.2024-1353

Graave, T., Li, Z., Lohrenz, T., & Fingscheidt, T. (2024). Mixed Children/Adult/Childrenized Fine-Tuning for Children’s ASR: How to Reduce Age Mismatch and Speaking Style Mismatch. Interspeech 2024, 5188-5192. https://doi.org/10.21437/Interspeech.2024-499

Graham, C., & Roll, N. (2024). Evaluating OpenAI’s Whisper ASR: Performance analysis across diverse accents and speaker traits. JASA Express Letters, 4(2), 025206. https://doi.org/10.1121/10.0024876

Kheddar, H., Hemis, M., & Himeur, Y. (2024). Automatic Speech Recognition using Advanced Deep Learning Approaches: A survey. Information Fusion, 109, 102422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2024.102422

Kuhn, K., Kersken, V., Reuter, B., Egger, N., & Zimmermann, G. (2023). Measuring the Accuracy of Automatic Speech Recognition Solutions. ACM Transactions on Accessible Computing, 16(4), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1145/3636513

Li, J., Hasegawa-Johnson, M., & McElwain, N. L. (2024). Analysis of Self-Supervised Speech Models on Children’s Speech and Infant Vocalizations (arXiv:2402.06888). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2402.06888

Liu, W., Qin, Y., Peng, Z., & Lee, T. (2024). Sparsely Shared LoRA on Whisper for Child Speech Recognition (arXiv:2309.11756). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2309.11756

Rolland, T., & Abad, A. (2024). Towards improved Automatic Speech Recognition for children. IberSPEECH 2024, 251-255. https://doi.org/10.21437/IberSPEECH.2024-51

Shi, Z., Srivastava, H., Shi, X., Narayanan, S., & Matarić, M. J. (2024). Personalized Speech Recognition for Children with Test-Time Adaptation (arXiv:2409.13095). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2409.13095

Xu, A., Feng, T., Kim, S. H., Bishop, S., Lord, C., & Narayanan, S. (2025). Large Language Models based ASR Error Correction for Child Conversations (arXiv:2505.16212). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2505.16212

Zhang, Y., Yue, Z., Patel, T., & Scharenborg, O. (2024). Improving child speech recognition with augmented child-like speech. 5183-5187. https://doi.org/10.21437/Interspeech.2024-485

Carr, A. N., Berthet, Q., Blondel, M., Teboul, O., & Zeghidour, N. (2021). “Self-Supervised Learning of Audio Representations from Permutations with Differentiable Ranking.” arXiv:2103.09879.

Shivakumar, P. G., Potamianos, A., Lee, S., & Narayanan, S. (2020). Transfer learning from adult to children for speech recognition: Evaluation, analysis, and recommendations. Computer Speech & Language, 63, 101077. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csl.2020.101077

Horii, K., Tawara, N., Ogawa, A., & Araki, S. (2025). Why is children’s ASR so difficult? Analyzing children’s phonological error patterns using SSL-based phoneme recognizers. Interspeech 2025. https://www.isca-archive.org/interspeech_2025/horii25_interspeech.pdf

Neuman, A. C., Wroblewski, M., Hajicek, J., & Rubinstein, A. (2010). Combined effects of noise and reverberation on speech recognition performance of normal-hearing children and adults. Ear and Hearing, 31(3), 336-344. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181d3d514

Kathania, H. K., Das, R. K., & Li, H. (2022). A formant modification method for improved ASR of children’s speech. Speech Communication, 135, 51-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.specom.2021.11.004

Johnson, A., Fan, R., Morris, R., & Alwan, A. (2022). LPC Augment: An LPC-based ASR data augmentation algorithm for low and zero-resource children’s dialects. arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.09529. https://arxiv.org/abs/2202.09529

Balaji, S., Fan, R., Morris, R., & Alwan, A. (2025). CHSER: A dataset and case study on generative speech error correction for child ASR. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.18463. https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.18463

Jain, A., Barcovschi, A., Yiwere, K., Bigioi, E., & Gales, M. (2022). A Wav2Vec2-based experimental study on self-supervised learning methods to improve child speech recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.05419. https://arxiv.org/abs/2204.05419