Research Report

Executive Summary

In an effort to assess the difference between the accuracy of speech-to-text models on child voices compared to adult voices, this report describes the extent to which Whisper, the state-of-the-art open weight ASR model, can be adapted for child speech through finetuning procedures. Two datasets were selected that contain audio data of children speaking alongside reference transcripts. After preparing the data, both models were finetuned using the same hyperparameters. This research found that finetuning Whisper speech-to-text models on child voice datasets reduces the error rate by 12-30% on a held-out testing portion of the same dataset. Substantial improvements in speech-to-text for child voices can be made through traditional finetuning procedures.

The gap between child and adult ASR cannot be pinned down precisely. We can infer it to be at 8x as many errors or 3x as many errors, depending on whether we look at a pair of similar datasets or a large collection of adult and child voice datasets. The improvement from finetuning is similarly difficult to pin down. One study found a 20% reduction in WER, which hardly closes the gap at all, while another study found an averaged 70% reduction in WER across multiple child voice datasets, which more than eliminates the gap. A firm answer to these questions would require a matched dataset and additional research, but a carefully finetuned model could largely eliminate the performance gap for child voice data with clear audio.

Introduction

Modern automatic speech recognition (ASR) systems perform less well for child voices, which hinders their ability to address a number of challenges in assessment and instruction.

This report describes the extent to which Whisper, the state-of-the-art open weight ASR model, can be adapted for child speech through finetuning procedures. Two datasets were selected that contain audio data of children speaking alongside reference transcripts. The baseline performance of the Whisper model will be reported alongside the performance of the same model after finetuning on a portion of each dataset. Finally, the baseline and finetuned performance will be compared against results for adult voice datasets from previous studies.

Methodology

Datasets

MyST (My Science Tutor) Corpus

The MyST corpus is a large collection of children’s conversational speech, comprising approximately 400 hours of audio data in 230,000 utterances across 10,500 virtual tutor sessions. The corpus was collected from around 1,300 students in grades 3-5 over a 13-year period (2007-2019). The data consists of spoken dialogue between children and a virtual science tutor covering 8 areas of science content aligned with Full Option Science System (FOSS) modules. The corpus features American English conversational speech collected from students across the United States, as FOSS modules are used in over 100,000 classrooms in all 50 states. The speech is spontaneous and conversational, with students providing spoken explanations during dialogue sessions with the virtual tutor.

Audio recordings were captured in a classroom environment using close-talking noise-canceling microphones with a push-to-talk interface, where students pressed and held the spacebar while speaking. Of the total utterances, 100,000 have been transcribed at the word level. No additional demographic information is available due to the anonymization strategy. The corpus is freely available for non-commercial research use and is also licensed for commercial applications.

CSLU Kids (OGI Kids) Speech Corpus

The CSLU Kids corpus contains speech data from approximately 1,100 children ranging from kindergarten through grade 10, with roughly 100 gender-balanced participants per grade level. The data was collected at the Northwest Regional School District near Portland, Oregon. As such, the speech likely reflects Pacific Northwest regional characteristics. The corpus includes both prompted and spontaneous speech, with the protocol consisting of 205 isolated words, 100 prompted sentences, and 10 numeric strings.

Speech was recorded using head-mounted microphones. Prompts were delivered using an animated 3D character called “Baldi” that provided synchronized visual and auditory cues. Each participant contributed approximately 8-10 minutes of recorded speech. Additional demographic information (languages spoken, age, physical conditions affecting speech production) was collected but has not been made available in the released version of the dataset. The corpus is freely available for research purposes.

Procedure

Audio file Splitting in CSLU Kids

Issue: The Whisper model can only process 30-second audio chunks. This makes training difficult when dealing with longer sequences. The CSLU Kids dataset needs to be split into 30-second or shorter chunks, but the transcript files lack timestamps, so it is not immediately clear how to keep the transcripts aligned with the newly segmented audio chunks.

Solution: Used the base Whisper model to generate transcripts with timestamps. While not perfectly accurate, these transcripts helped align the original transcripts to the newly sub-divided audio files.

- Timestamped transcripts were generated using the Whisper v3 large base model.

- Overlapping segments in the original gold reference transcript from CSLU Kids and the generated Whisper transcript were identified.

- Candidate segmentation locations were timepoints where the original transcript and the newly generated Whisper transcript overlapped perfectly.

- Audio files were split at the candidate segmentation location that was closest to 30 seconds without going over. The timestamp from the Whisper transcript was used to split the audio file. The original transcript was simultaneously split and saved as the reference transcript for the newly segmented audio files.

- The Whisper transcript was discarded.

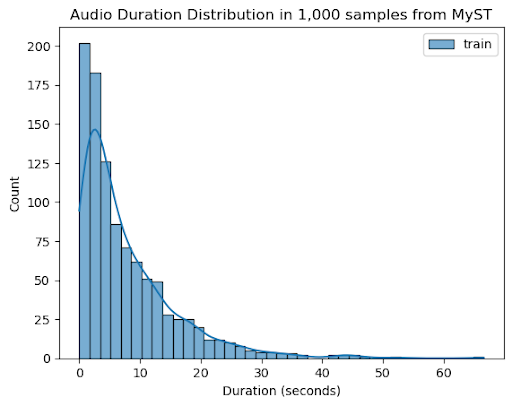

In MyST, audio samples longer than 30 seconds were removed, since they represented a small proportion of the overall dataset:

Data Preparation

The first step was transcript normalization. The same text normalization strategy was used for both datasets. The first step was to remove transcript annotations and metalinguistic information using regular expressions. For both datasets, these included all character sequences surrounded by angle brackets, such as “<pau>”, which indicates a pause. Additionally, false starts were removed. These were indicated in the original transcripts with an asterisk. For example, if the speaker begins to say a word starting with “th”, that would be indicated as “th*”. Initial testing indicated that the base Whisper models do not transcribe false starts, so these were also removed.

After annotations were removed, the Whisper English text normalizer was applied, as implemented in the HuggingFace transformers library (version 4.49). This text normalizer converts spelled out numbers to digit representations (twenty-fourth → 24th), converts British to American spelling (“colour” → “color”), removes excess whitespace (“three spaces” → “three spaces”), expands contractions (“can’t” → “cannot”), removes diacritics (“œ” → “oe”), and performs a handful of other standardization processes that standardize the transcript for use by Whisper models.

Each dataset was then partitioned for finetuning. After segmentation, MyCSLU was partitioned with an 80/20 split, which resulted in 6,111 train samples and 1,528 test samples. The MyST release dataset provides train, validation, and test partitions. These partitions were used without modification. The data was then filtered to remove samples longer than 30 seconds, shorter than 5 seconds, or samples that had empty transcripts after normalization. The resulting filtered dataset had 36,544 training samples and 6,321 samples in the testing set. The validation set was not used, as no hyperparameter optimization was conducted.

Metric

Performance is reported in terms of weighted word error rate (WER), which is the percentage of inaccurate words divided by the number of words in the reference transcript. Typically, WER would be calculated for each sample and averaged across the dataset. This presents a problem when samples are of varying length because shorter samples are less informative about model performance. A simple solution to this problem is to use a weighted average WER, which simply weights the WER of each sample by the number of words in the sample. This is equivalent to calculating WER for all samples in the test set at once. All reported results are in terms of weighted WER.

Finetuning Setup

Both models were finetuned using the same hyperparameters, selected a priori after reviewing previous work on finetuning Whisper. These values were adjusted downwards to constrain training time and minimize risk of catastrophic forgetting. The values utilized for finetuning were: warmup steps = 100, learning rate = 1e-6, effective batch size = 16 (batch_size = 8, gradient accumulation steps = 2), and max_steps = 1,000.

A GitHub repository including all research code is publicly available here: https://github.com/langdonholmes/asr-finetune

Findings

CSLU Kids

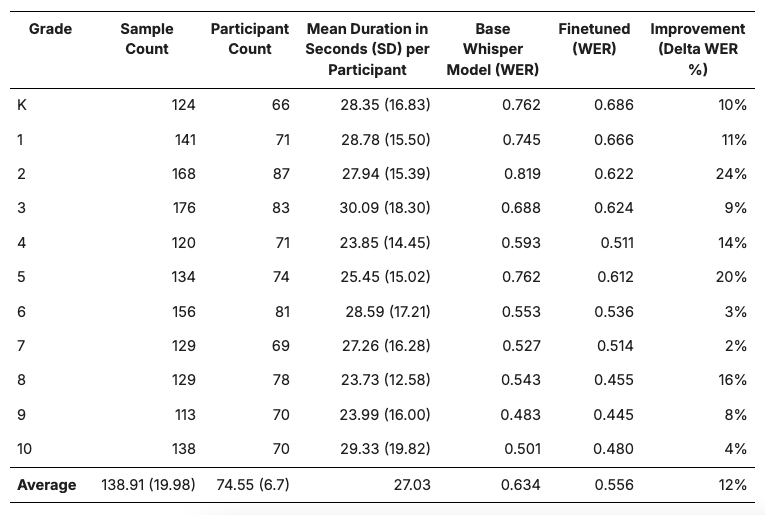

Baseline WER: 0.634

Finetuned WER: 0.556

Reduction in WER: 12%

CSLU Kids by Grade Level

Finetuning improved performance most for the K-5 range, with a notable exception at the 8th grade level.

MyST

The MyST test set contained 6,321 samples with an average length of 11.79 seconds (SD=5.77). These samples were sourced from 91 speakers, who contributed an average of 819.19 seconds (SD=707.81).

Baseline WER: 0.20

Finetuned WER 0.14

Reduction in WER: 30%

Note: All data in MyST was sourced from 3rd-5th grade students, and no grade level data is available on a per-speaker basis.

Comparison with Adult Voices

It is difficult to quantify the ASR performance gap between child and adult voice data, since a dataset of matched child and adult voices does not exist. However, Whisper has been shown to generate transcripts with a word error rate (WER) as low as 3% on a dataset of adults reading aloud (Radford et al., 2022). The same model when applied to a dataset of children reading aloud produced a WER of 25% (Graave et al., 2024). That is eight times as many errors. Graave et al. reduced the WER for that same dataset down to 20% using a combination of finetuning strategies, but that is still seven times as many errors as the comparison adult voice dataset. This paints a bleak picture for the performance improvement that can be had through finetuning.

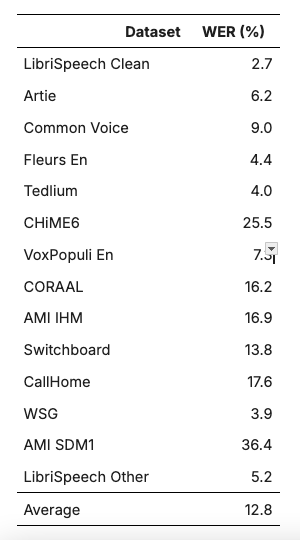

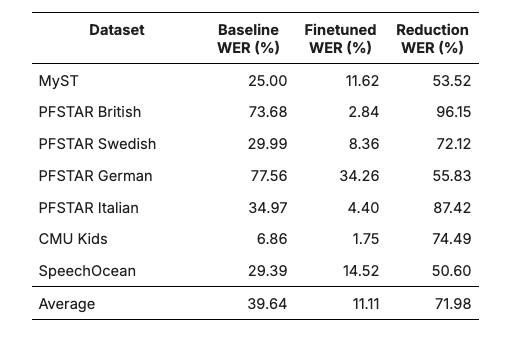

We can paint a rosier picture by looking at different datasets. ASR performance varies substantially across datasets for both adult and child voices, as shown in Tables 2 and 3. This makes it difficult to assess how much performance is negatively impacted by characteristics specific to child voices. However, the mean performance of Whisper v2 Large across 14 datasets is 12.8% WER, and one study (Jann et al., 2024) was able to reduce Whisper’s error rate down to 11.11% WER across seven child voice datasets, as shown in Table 3. Without finetuning, the child datasets result in a WER of 39.64%, which is a gap of 27% or about three times as many errors as seen in the collection of adult voice datasets. With finetuning, the gap completely disappears, as measured WER is better on average for the child voice datasets.

The performance improvement in Jain et al. was achieved through a combination of dataset augmentation strategies and sampling strategies such as beam search that were applied after finetuning. The finetuned WER reproduced in Table 3 is from the same model applied to the test set of each dataset. That model was finetuned on a mixture of data from the training partitions of all the listed datasets. Their results indicate that finetuning can substantially improve ASR performance, and it appears that a single finetuned model has the potential to generalize to unseen child voice datasets.

Despite these results, it is important to note that strong statements about the ASR gap between child and adult voices are not possible because no matched data exists. We can make inferences based on the available data, but the high variability between datasets weakens the strength of these inferences. This gets even murkier when we involve finetuning and ask the question, “How much is the gap reduced by finetuning?”. If we finetune a model on a child voice dataset and test it on that same dataset, the performance improvement can come from things that are not just the model being better at transcribing child voices. The model will also learn quirks of the dataset, like dataset-specific transcription guidelines, background noise profiles, and even the words used (since recordings from the same dataset usually belong to the same genre and maybe even share a topic/theme). Likewise, if we test the model on a different child voice dataset, then differences in these variables could hurt model performance, similarly obfuscating results.

Studies such as Jain et al. (2024) have shown that a model finetuned on one child voice dataset can show improved performance on a variety of child voice datasets. This is good reason to believe that some of what the model is learning is really and truly how to transcribe children’s voices in a general sense, but it is not possible to quantify this figure precisely without data collected for this specific purpose. That data would involve a collection of adult voice recordings doing something predictable like reading aloud and a collection of child voices doing the same thing, recorded in the same way, and transcribed according to the same rules.

Limitations

The CSLU Kids dataset was segmented into chunks less than thirty seconds long using an automated approach. This approach involved using an imperfect transcript with imperfect timestamps (generated with the Whisper base model) and comparing it to the ground truth reference transcript. By segmenting the audio on areas of agreement, the risk of a misaligned transcript was minimized, but not eliminated. Misalignments in the segmented transcript could have inflated both the baseline and finetuned WER. With well-aligned transcripts, it is likely that both WER values would be lower, which would increase the observed reduction in WER accordingly. We observed an improvement of 0.08, which was 12% of 0.634, but that same improvement of 0.08 would be 24% out of a WER of 0.317. This indicates that the metrics of improvement in WER % is sensitive to potential issues with the alignment strategy. Of course, it would be preferable to source finetuning data in chunks of less than 30 seconds with transcripts that are known to be well-aligned with the audio.

Word error rate (WER) is a standard metric in ASR evaluation. However, it has limitations particularly when comparing performance across distinct datasets. WER treats all errors equally, regardless of their phonological or semantic significance. This ignores whether errors reflect acoustic confusion, linguistic processing failures, or developmental speech patterns typical of younger speakers. That said, WER remains valuable for tracking relative improvements within a controlled dataset, as in the finetuning experiments presented here, since confounding variables remain consistent across dataset partitions. Still, future work might seek to gain deeper insight into the nature of performance disparities between child and adult ASR by incorporating complementary metrics. Phoneme error rate (PER) would better capture acoustic-phonetic confusions that differ between age groups, while semantic similar measures could reveal whether errors preserve meaning. Character error rate (CER) would be more robust than WER to minor morphological variations that may not impede meaning.

Recommendations

Substantial improvements in speech-to-text for child voices can be made through traditional finetuning procedures, as demonstrated by the 12-30% reduction in error rates on child voice datasets.

Further research should be conducted to assess whether a general-purpose finetuned model can be developed that would generalize to child speech data in diverse settings. The improvements in word error rate (WER) observed here can be attributed to multiple factors. Since the models were developed and tested on the same datasets, some performance improvement is likely attributable to learning the specifics of the transcription conventions, the recording scenario, and the content areas. A general-purpose child voice ASR model would show improved performance with diverse child voice data. Future development work should finetune models on child voice data sourced from multiple contexts (or multiple different datasets) and evaluate performance on diverse test sets or test sets that do not closely reflect the characteristics of the finetuning data.

When considering whether ASR models like Whisper can be finetuned to perform as well for child voices as they do for adult voices, a related question is whether human annotators are as accurate with child voice data as adult data. For any future work that involves transcribing child voice data, it will be useful to collect annotator agreement data. This data can be used to test how well ASR models compare relative to human annotators. Across many tasks, the upper limit on performance for finetuned models is the inter-annotator agreement of the data that they are trained on (Mayfield and Black, 2020).

Conclusion

Finetuning the Whisper speech-to-text model on child voice datasets substantially reduces the word error rate, demonstrating that traditional finetuning procedures can lead to improvements for child voices. Further research is warranted to compare these findings with previous studies (including studies on adult voice datasets) and to explore the development of a generalized finetuned model adaptable to diverse child speech settings.

Langdon Holmes

References

Graave, T., Li, Z., Lohrenz, T., & Fingscheidt, T. (2024). Mixed Children/Adult/Childrenized Fine-Tuning for Children’s ASR: How to Reduce Age Mismatch and Speaking Style Mismatch. 5188–5192. https://doi.org/10.21437/Interspeech.2024-499

Jain, R., Barcovschi, A., Yiwere, M. Y., Corcoran, P., & Cucu, H. (2024). Exploring Native and Non-Native English Child Speech Recognition With Whisper. IEEE Access, 12, 41601–41610. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3378738

Mayfield, E., & Black, A. W. (2020). Should you fine-tune BERT for automated essay scoring? Proceedings of the Fifteenth Workshop on Innovative Use of NLP for Building Educational Applications, 151–162. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2020.bea-1.15

Radford, A., Kim, J. W., Xu, T., Brockman, G., McLeavey, C., & Sutskever, I. (n.d.). Robust Speech Recognition via Large-Scale Weak Supervision.